The New Antiquity

Living for the first time in an ancient city on a Rome Prize Fellowship in 2008, I began to notice a shift in attention when looking at archeological sites. I took that forceful change in significance to parts of the city that are not so well documented.

The photographs in The New Antiquity were made over five years, in the suburbs of great and ancient capitals, in Italy and China, and then along the eastern seaboard of the United States. They portray a world where layers of time are collapsed. Places of great antiquity turn up on digital camera screens and sugar packets and in front of apartment blocks. New buildings and structures and objects seem to be decaying into what Davis calls “a soon to be ancient past.” People appear, but they are difficult to place in time. There are red herrings: pictures that look like archeology, but might just be the side of the road. And there are places of real antiquity, but seen without romance, as living things. Intended as a complex and open-ended work of “creative non-fiction,” the pictures in this body of work, made with a large-format camera, are both beautifully clear and vehemently obscure.

Golf

Fresco

Angel Armor

Glamorous Hair

Ball and Vines

Girls

Gypsy Meal

Mechanic

Motel Boomerang

New Buddhas

Shanghai

Shopping Cart

Skull

Sneaker Sole Store

Teeth

Wooden Toy Factory

Xiamen Mansard

Birdshit

Bumpers

Cat Chaplin

Ciao Logs

Diorama

Fluorescent Cleat

Gold Flecked Web

Guts

Immigrants Snapshots

Modernist Reflection

Moustache Statue

Orange Boxes

Pearl Animals

Seranflex

Statue of Pants

Sugarcane Burning

Tile Road

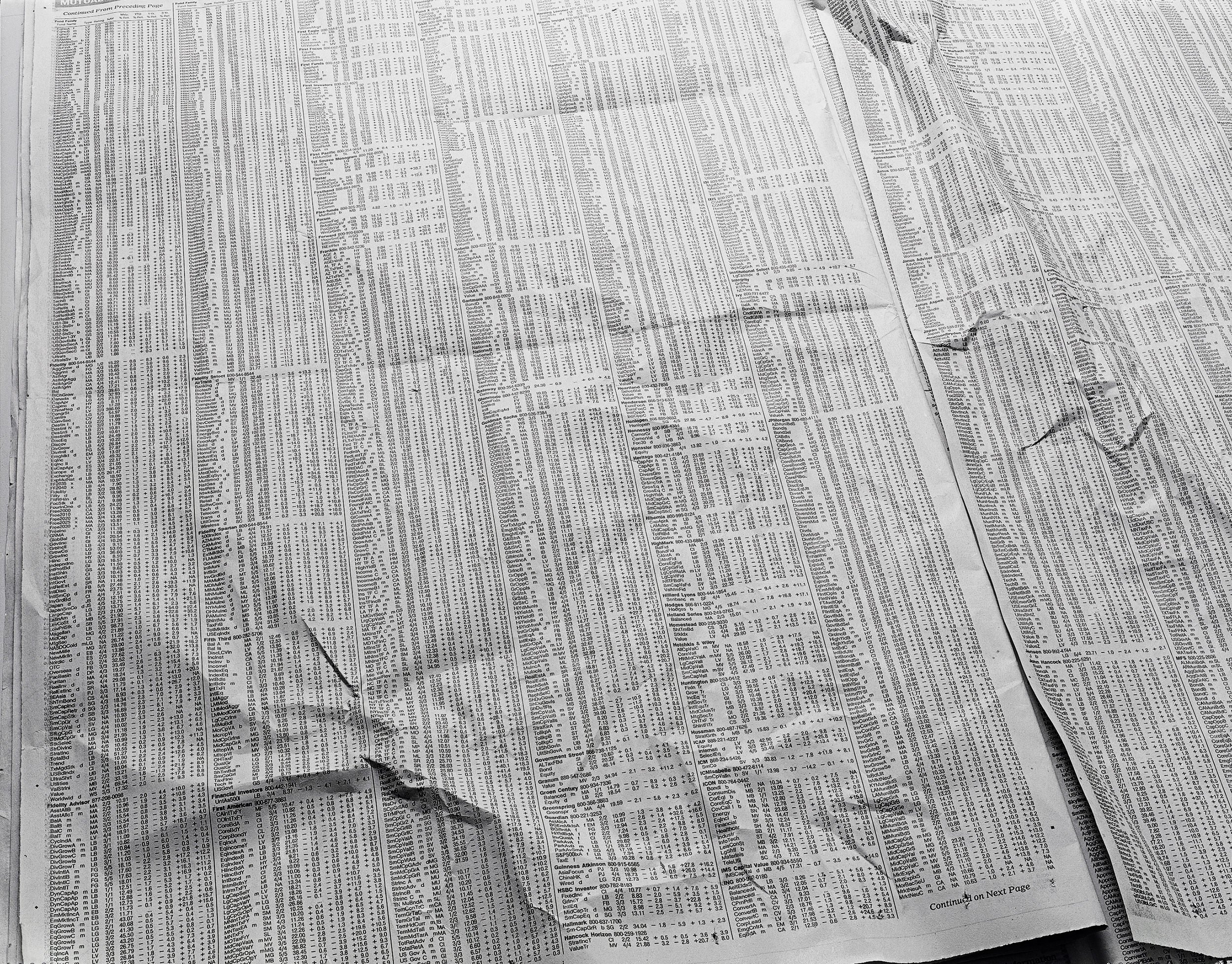

Stock Pages

The New Antiquity

An Essay By Tim Davis

You are standing in a field in Italy, looking at a pile of rocks.

They are unremarkable, rutting out the ground like any gentle reminder that we live on something called a “crust.” You’ve seen rocks and these are rocks. But someone else—a friend, a guidebook, a scholar—sees a temple, an Etruscan temple of characteristic proportions carved from something called “tufa” and consecrated to Fufluns, a wine god. You don’t exactly see a temple, but sense that these rocks—as integral to the ecosystem of any vacant Roman lot as seasonal chicory and perennial used condoms—are suddenly significant. They mean something they stubbornly refused to mean minutes before.

During a recent stint in Rome (on a Rome Prize Fellowship), photographer Tim Davis became drawn to the peculiar status of ancient ruins. "You are standing in a field in Italy, looking at a pile of rocks. You've seen rocks and these are rocks. But someone else-a friend, a guidebook, a scholar-sees a temple . . ." Fascinated with the degree of meaning making that we bring to bear upon such minimal visual cues, Davis tested this perceptual shift on suburban ruins-what he calls "a soon-to-be ancient past"-and found that it was possible to make pictures that "look like archaeology, but might just be the side of the road."